First of all : THANK YOU !!! Thank you so much for being here and reading my blog on this auspicious day.

Auspicious as in : Today would have been the First day of the biggest wool show in the southern hemisphere which was a super major part of my life for the last almost 2 decades!

Because of these Covidian times (let’s make this a word…lol) there are no shows, let alone a sheep and wool show where thousands and thousands of people FLOCK to sellers of wool and yarns and support small farms like ours.

I knew July was going to be a tough one for me and it is. And, it will be for a long time July ends after. The income from the show provides long term investment possibilities to make sure that farms can secure feed, infrastructure and care. The revenue from a big wool show like that is not going to a so called “holiday fund to spend time skiing or lounging on a beach”. Let’s face it: small farmers don’t tend to have holidays at all… it goes straight back into the farm and their animals. Same here. So any income lost at this time, will impact for a long time to come. A long time after the crisis has passed. So yeah, I am super happy to have you here, spending some time on my weekly blog reading about me and what I am doing and what new fluffy things I have come up with to entice and enable you !

I hope you have set aside some time for this week’s blog because it is going to be a very LOOOOOOOOOOOONG one !!!! A long and exciting one with heaps of things that hopefully will put a smile on your face and get to know more of certain rare breeds, my efforts to bring them to you and also a NEW yarn range that will knock your socks off…lol

Also, to make this update extra special :

Everybody who purchases over the weekend will receive their order reference number which will also act as a lucky lottery ticket !!! It will give you the chance to win a fantastic fluffy surprise parcel worth more than $200 !!

The winner will be announced on my blog update of July 24th !!!

I have been running this kind of thing every year at the Bendigo Show and I am not stopping now ! A random number generator will pick the lucky winner ! Good luck to everybody !!!

For tonight’s update I have a LOT of fibery and yarny adventures to offer you:

1. ViVa Frida Tops: An exclusive Rare sheep breed blend of Navajo Churro Sheep and agave cactus blended with cashmere and angora bunny into an amazing top which is great to spin and wear. Great for socks!!! Great for anything !!!

2. A Rare breed sheep top: Castlemilk moorit from Scotland and super fab to spin

3. Vicuna blend tops: this is too rare and fantastic for words! I rarely can offer this because it is so rare and expensive !!!

4. IxCHeL Cashmerino lace yarn on cones!!! FAB for knitting, weaving and felting !!! I do not normally offer this on cones !! 100grams I normally sell for $32, this weekends special price is $129 !! for a kilo + cone !!!

5. NEW TWEED YARN RANGE !!! So, get a cuppa or a glass of wine! Put your feet up and enjoy a Fibre and yarn fest right here on the IxCHeL blog !!!

A little history on why I came up with putting these particular fibres together: I have spent a lot of time working in Mexico, in and around Toluca and Pueblo and even more time soaking up the wonders of Yucatan and Oaxaca. I knew that there was trade in the far past between the Navajo Nation and the Aztec, Mixtec and Mayan communities, especially when weaving was concerned. So that is when I thought of this new blend combining a plant fibre used by both cultures and the ever important Churro sheep of the Navajo Nation: into existence came my quest to create a blend of both cultures that have meant so much to me in my fibre art: the Agave plant (Maguey) and the Navajo Churro.

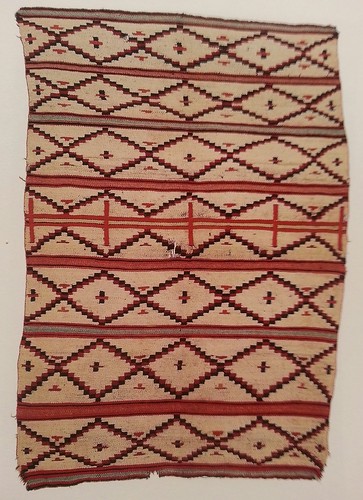

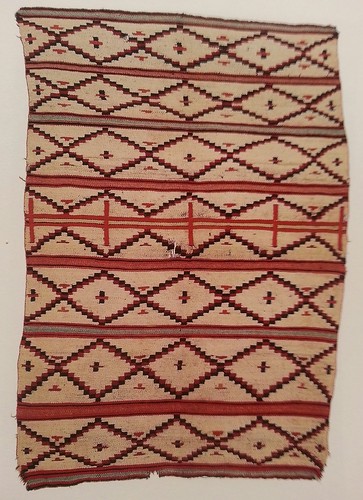

You may know I have a soft spot for Navajo Churro sheep and the navajo rugs. Spending a substantial time of my childhood spinning and rugs being woven and the stories being told. I guess that is what is really the most important: the stories that are so intrinsically woven into the yarn and the rugs and the making of warps and baskets.

It is not only a craft , but also a way of translating how we look at the world and incorporate its magic into a two dimensional framework. Even the way that we see looms are different: the ropes to hold the warp threads are the thunder and the the warp itself is the rain falling down from heaven to earth. I was always taught never to weave when there was a lightning storm because of that.

Ofcourse sitting at a large loom , exposed to the elements , is never an extremely good idea when a big lightning storm hits, but you see how it all interweaves into ones life. Everything has a meaning, everything around you is transformed and has its own magic. Just look at how the corn rug below resembles reality...abstract and yet so similar.

There are so many things going on in a navajo rug, whether it be something minuscule woven into certain spots like a feather into a horse blanket to make sure that the horse is fast as an eagle, or bits of hair or plants, all have their meaning.

In the old days , the midwife collected corn pollen and then a horny toad was found and the pollen was put on its head and mouth. It was an extremely good omen that the toad spat out the corn mush and often that is why these kinds of ceremonial birthing rugs have yellow woven in to them, much like this one here:

Auspicious as in : Today would have been the First day of the biggest wool show in the southern hemisphere which was a super major part of my life for the last almost 2 decades!

Because of these Covidian times (let’s make this a word…lol) there are no shows, let alone a sheep and wool show where thousands and thousands of people FLOCK to sellers of wool and yarns and support small farms like ours.

I knew July was going to be a tough one for me and it is. And, it will be for a long time July ends after. The income from the show provides long term investment possibilities to make sure that farms can secure feed, infrastructure and care. The revenue from a big wool show like that is not going to a so called “holiday fund to spend time skiing or lounging on a beach”. Let’s face it: small farmers don’t tend to have holidays at all… it goes straight back into the farm and their animals. Same here. So any income lost at this time, will impact for a long time to come. A long time after the crisis has passed. So yeah, I am super happy to have you here, spending some time on my weekly blog reading about me and what I am doing and what new fluffy things I have come up with to entice and enable you !

I hope you have set aside some time for this week’s blog because it is going to be a very LOOOOOOOOOOOONG one !!!! A long and exciting one with heaps of things that hopefully will put a smile on your face and get to know more of certain rare breeds, my efforts to bring them to you and also a NEW yarn range that will knock your socks off…lol

Also, to make this update extra special :

Everybody who purchases over the weekend will receive their order reference number which will also act as a lucky lottery ticket !!! It will give you the chance to win a fantastic fluffy surprise parcel worth more than $200 !!

The winner will be announced on my blog update of July 24th !!!

I have been running this kind of thing every year at the Bendigo Show and I am not stopping now ! A random number generator will pick the lucky winner ! Good luck to everybody !!!

For tonight’s update I have a LOT of fibery and yarny adventures to offer you:

1. ViVa Frida Tops: An exclusive Rare sheep breed blend of Navajo Churro Sheep and agave cactus blended with cashmere and angora bunny into an amazing top which is great to spin and wear. Great for socks!!! Great for anything !!!

2. A Rare breed sheep top: Castlemilk moorit from Scotland and super fab to spin

3. Vicuna blend tops: this is too rare and fantastic for words! I rarely can offer this because it is so rare and expensive !!!

4. IxCHeL Cashmerino lace yarn on cones!!! FAB for knitting, weaving and felting !!! I do not normally offer this on cones !! 100grams I normally sell for $32, this weekends special price is $129 !! for a kilo + cone !!!

5. NEW TWEED YARN RANGE !!! So, get a cuppa or a glass of wine! Put your feet up and enjoy a Fibre and yarn fest right here on the IxCHeL blog !!!

VIVA FRIDA TOPS with Navajo Churro sheep

A little history on why I came up with putting these particular fibres together: I have spent a lot of time working in Mexico, in and around Toluca and Pueblo and even more time soaking up the wonders of Yucatan and Oaxaca. I knew that there was trade in the far past between the Navajo Nation and the Aztec, Mixtec and Mayan communities, especially when weaving was concerned. So that is when I thought of this new blend combining a plant fibre used by both cultures and the ever important Churro sheep of the Navajo Nation: into existence came my quest to create a blend of both cultures that have meant so much to me in my fibre art: the Agave plant (Maguey) and the Navajo Churro.

Frida in a photo session with a majestic Agave plant

You may know I have a soft spot for Navajo Churro sheep and the navajo rugs. Spending a substantial time of my childhood spinning and rugs being woven and the stories being told. I guess that is what is really the most important: the stories that are so intrinsically woven into the yarn and the rugs and the making of warps and baskets.

It is not only a craft , but also a way of translating how we look at the world and incorporate its magic into a two dimensional framework. Even the way that we see looms are different: the ropes to hold the warp threads are the thunder and the the warp itself is the rain falling down from heaven to earth. I was always taught never to weave when there was a lightning storm because of that.

Ofcourse sitting at a large loom , exposed to the elements , is never an extremely good idea when a big lightning storm hits, but you see how it all interweaves into ones life. Everything has a meaning, everything around you is transformed and has its own magic. Just look at how the corn rug below resembles reality...abstract and yet so similar.

There are so many things going on in a navajo rug, whether it be something minuscule woven into certain spots like a feather into a horse blanket to make sure that the horse is fast as an eagle, or bits of hair or plants, all have their meaning.

In the old days , the midwife collected corn pollen and then a horny toad was found and the pollen was put on its head and mouth. It was an extremely good omen that the toad spat out the corn mush and often that is why these kinds of ceremonial birthing rugs have yellow woven in to them, much like this one here:

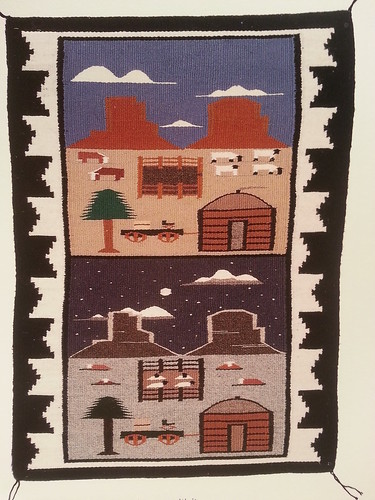

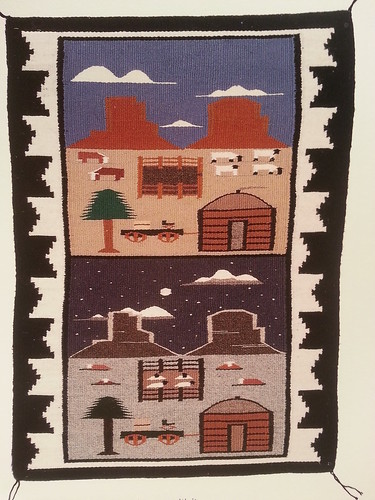

Night times; daytime rug

Weaving and spinning yarn is more than just a craft to me and the Navajo people. It is an expression of culture. The yarns are used to weave the rich history and tell the stories and this history is passed down from generation to generation. There was lots of trade between the Aztic, Mixtec and Navajo people, and the weaving tradition of the Navajo was certainly influenced by it.

The rugs sing a song, tell a story and that is what makes them so magical. If the past and the stories are forgotten, then the rugs won’t mean anything. Not only are there rugs but also other items that are woven : baskets and so called Tump line weavings ( an object woven with a warp of Agave and wool or just agave fibres) , worn over the head to help carry heavy loads) Here is a photo of one that survived from the pre-columbian times (= pre 1500s)

The rugs sing a song, tell a story and that is what makes them so magical. If the past and the stories are forgotten, then the rugs won’t mean anything. Not only are there rugs but also other items that are woven : baskets and so called Tump line weavings ( an object woven with a warp of Agave and wool or just agave fibres) , worn over the head to help carry heavy loads) Here is a photo of one that survived from the pre-columbian times (= pre 1500s)

But now back to the Viva Frida tops I offer you today : a passionate blend of Agave ( used for weaving , making tequila and Mezcal: please do not try to drink this blend ;-) ) and the Navajo Churro rare sheep breed.

Navajo Churro sheep are very special just like the history they have : The Navajo call them "the Old Ones" and see the Churro sheep as a gift from the Gods. The wool from these sheep are the basis of the Navajo Weaving and also is a wonderful fibre to make socks and ponchos. The sheep were nearly wiped out during the tribe's forced relocation in the 1860s and again in the stock reductions of the 1930s: federal agents just went from hogan to hogan and shot a large percentage of the livestock and horses, more than 250.000 animals were killed and the Churro sheep were almost extinct with fewer than 700 head by 1990! But they are making a comeback, due to the efforts of the Navajo Sheep Project so they can return to their historic place and purpose among the Navajo and that it can benefit the Navajo People. The hand dyed tops that I am offering you here are blends of soft white Churro fleece with Angora Bunny: it makes for a wonderful mix and will make the most wonderful yarn, suited for socks and outerwear as well as sweaters. The Bunny and the Cashmere added to the Churro makes it very soft to handle and very easy to spin.

The Agave , or the Maguey as it is also called, has lots of different uses. Archeologists have found evidence that agave were used for food as far back as 9,000 years ago. The agave plant was used for cloth and fermented drink for at least the past 2,000 years. Agaves grow in a remarkable range of terrains and climates. They are found in forests, hillsides, arid plains, deserts and sea coasts, at altitudes extending from sea level to 2,400m (approx. 8,000 ft.).They can survive temperatures ranging from -9 to +41 degrees Celsius (about 15 to 106 degrees Fahrenheit ).

Agaves were the source of many essential items, including fibres for clothing, poultices for wounds, medicines, poisons for arrowheads, building materials and food. As food, the use dates back about 11,000 years based on archeological remains of cooked agave in pits. Even today, agave fibre is used for cloth and paper, although not nearly as much as the industry produces as waste from the tequila production. The agave provided so many essential materials and that it became known as El Arbol de las Maravillas (The Tree of Wonders).

Many Pre-Columbian people in Mesoamerica cultivated the agave. Domestic agaves included (popular names in parentheses): Agave zapota (sapodilla), Agave atrovirens (maguey), Agave fourcroydes (henequen), Agave latissima (maguey). Agave mapisaga (maguey). Agave sisalana (sisal) and Agave tequilana (tequil maguey).

In about 2,000 BCE, maguey was grown in Tula, Tulancingo and Teotihuacan, where obsidian scrapers have been found, suggesting the agave was used for aguamiel or pulque. The ancient Aztec riddle asked "What points its finger at the sky?" and the riddle's answer is "the Maguey Thorn."

When the Conquistador Hernan Cortez wrote to King Carlos V of Spain in 1520, he noted, "honey is also extracted from the plant called maguey, which is superior to sweet or new wine; from the same plant they extract sugar and wine, which they (the natives) also sell." In The Agaves of Continental North America, Howard Scott Gentry wrote, The hunting and gathering tribes had good reason to regard agaves with special attention, because agaves supplied them with food, fibre, drink, shelter, and miscellaneous natural products. Protection may have been one use, for when planted around a cottage, the larger species make armed fences, a common practice in modern Mexico. While much about the first beginnings of agriculture will always remain obscure, there is a great deal now known about the history of man-agave relationship.

In about 2,000 BCE, maguey was grown in Tula, Tulancingo and Teotihuacan, where obsidian scrapers have been found, suggesting the agave was used for aguamiel or pulque. The ancient Aztec riddle asked "What points its finger at the sky?" and the riddle's answer is "the Maguey Thorn."

When the Conquistador Hernan Cortez wrote to King Carlos V of Spain in 1520, he noted, "honey is also extracted from the plant called maguey, which is superior to sweet or new wine; from the same plant they extract sugar and wine, which they (the natives) also sell." In The Agaves of Continental North America, Howard Scott Gentry wrote, The hunting and gathering tribes had good reason to regard agaves with special attention, because agaves supplied them with food, fibre, drink, shelter, and miscellaneous natural products. Protection may have been one use, for when planted around a cottage, the larger species make armed fences, a common practice in modern Mexico. While much about the first beginnings of agriculture will always remain obscure, there is a great deal now known about the history of man-agave relationship.

The main source of food in agave is the soft starchy white meristem. in the short stem and the bases of leaves, excluding the green portion. As the plant matures the starch and sugar content of these organs increases, as does their palatability. Some species and varieties are more palatable than others; those with high sapogenin content and other toxic compounds were generally known and avoided. The young, turgid, tender flowering shoot of most species is edible, as are the flowers of many. The early agriculturist doubtless selected only the sweet sorts for cultivation. Since merely supplying heat converts the starches to sugars, the Indian cooked the softer parts by direct fire or with hot water. "Cooking appears to have been largely of the roasting type, with the outside frequently charred, and the interior still raw. This is true of such plants as Ceiba, Agave, and Opuntia, though they appear to have been eaten raw almost as frequently" (Callen, 1965). Charring of agave flowering shoots by laying them in the fire or in hot coals and ashes overnight was still observed among the backcountry Mexicans in the 1970s, especially to appease hunger on longer journeys. From the time the Mexicans had pots, these flowering shoots were probably boiled, a practice extended to modern times in Mexico. A more sophisticated or communal method for cooking agave was pit baking, which became universal, at least north of Mesoamerica, and which has been mapped and fully discussed by Castetter et al. (1938).

The Aztecs used agave fibre in the manufacture of an all-purpose sack called an 'ayate.' In 1531 an ayate was imprinted the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, since then the Patron of Mexico. In Hidalgo, the Otomis still make fabric from the agave; the men and boys separate fibre from leaves while the women and girls do the weaving.

Prehistoric and historic Indian archeological sites in the Southwest USA show evidence for agave roasting pits, as well as some evidence for agave agriculture. Prehistoric peoples in the Sonoran Desert may have transported agave pups from as far away as Mesoamerica (the great city states in southern Mexico) and may have planted tens of thousands of these agaves in fields that covered square miles in the northern Tucson Basin. The Arizona-Sonoran Desert Museum internet site says the Indians of the Hohokam Puebloan tradition cultivated the Hohokam agave in areas that covered hundreds of thousands of acres: "All of the agave populations from Caborca, Sonora, to New River, Arizona, are so similar that they may be one genetic clone.” Agave was considered sacred by many Pre-Hispanic people. The oldest records come from the Aztec codex, the Tonalmatl Náhuatl, ("Aztec pilgrim's papyrus"), which tells the story of the Mexican people. According to the codex of Nutall, Laud, Florentino and Mendocino, natives had many different uses for agave and its sub-products: food, threads, needles, shoes, roof tops, clothes, nails, weapons and paper among others. The seeds have been ground into powder to make bread or to thicken soup.

In 1577, the Spanish explorer Francisco Hernández wrote about the maguey in the central highlands of Mexico: "As a whole (maguey) can be used as fuel or to fence fields. Its shoots can be used as wood and its leave as roofing materials, as plates or platters, to make paper, to make cord with which they make shoes, cloth, and all kinds of clothes…. From the sap…they make wines, honey, vinegar, and sugar…From the root, they also make very strong ropes which are useful for many things. The thicker part of the leaves as well as the trunk, cooked underground…are good to eat…There is nothing which gives a higher return."

The agave is still used as food today, although it is not as critical to the natives as it was in the past. Agave syrup or nectar (aguamiel) has always been popular in Mexico, but in the past decade has become popular in the health food circles because it provides a good alternative to cane sugars that diabetics can also tolerate.

For millennia, the Hnahnu people used the agave as a source of material to produce more 100 different products including fibres for weaving, brushmaking and other crafts, construction materials, soap, small furniture, toys, ornaments, food and beverages, paper, medicinal products, firewood and even boundary markers in the countryside. The Hnahnu retain a deep traditional knowledge of the life-cycle, characteristics and uses of the agave.

Agave is still used as medicine, particularly in boticas - pharmacies - usually in alternative medicine boticas that offer natural or homeopathic remedies, often selling them beside religious icons and images on the same shelf. One botica online promises agave essence will cure "emotional immaturity, aggressive conduct, impatience, fatigue and premature aging. Before the mid-1800s, there were a dozen agave species used for tequila. But the producers were specializing, growing those that made the best economic as well as aesthetic product.

By the 1870s, the indigenous people of Mexico had so refined their cultivation practices that physiological ecologists of today have barely bettered them. By the 1870s tequila was reduced to the monoculture of blue agaves. In March, 2007, scientists at the University of Guadalajara have announced they believe the blue agave contains compounds that may be useful in carrying drugs to the intestines to treat diseases such as Crohn's disease and colitis.

Perhaps the biggest potential market for agave food products today is the growing agave nectar or syrup market. Agave syrup consists primarily of mostly the easily digested fructose and s smaller percentage of glucose, the amounts depending on the producer. It is sold as a sugar substitute in many health and grocery stores (agave syrup is three-four times sweeter than table sugar). While similar to honey, agave nectar's glycemic index is only 27, compared to honey at 83, which means it is absorbed more slowing into the bloodstream.

And ofcourse, the Agave is also used to produce Mezcal and Tequila !

But enough of sugar and other contents, I assure you that spinning this fibre blend does not impact negatively on your calory intake..lol .

A beautiful blend of Navajo Churro, Agave Cactus, Cashmere, angora bunny

100grams AU$25

Cosmic Wave SOLD

Cosmic Wave SOLD

A sunny Beach day SOLD

A sunny Beach day SOLD

Vampire Weekend ...sold

Vampire Weekend ...sold

Flamingoes in the Caribbean SOLD

Flamingoes in the Caribbean SOLD

Lavender Fields SOLD

Dragonfly in Amber Sold

Dragonfly in Amber Sold

Indigo SOLD

Indigo SOLD

Rose Velvet-SOLD-

Rose Velvet-SOLD-

Rainforest Dreams SOLD

Rainforest Dreams SOLD

Gem Corn Magic SOLD

Gem Corn Magic SOLD

Unicorn Puppies SOLD

Unicorn Puppies SOLD

Prehistoric and historic Indian archeological sites in the Southwest USA show evidence for agave roasting pits, as well as some evidence for agave agriculture. Prehistoric peoples in the Sonoran Desert may have transported agave pups from as far away as Mesoamerica (the great city states in southern Mexico) and may have planted tens of thousands of these agaves in fields that covered square miles in the northern Tucson Basin. The Arizona-Sonoran Desert Museum internet site says the Indians of the Hohokam Puebloan tradition cultivated the Hohokam agave in areas that covered hundreds of thousands of acres: "All of the agave populations from Caborca, Sonora, to New River, Arizona, are so similar that they may be one genetic clone.” Agave was considered sacred by many Pre-Hispanic people. The oldest records come from the Aztec codex, the Tonalmatl Náhuatl, ("Aztec pilgrim's papyrus"), which tells the story of the Mexican people. According to the codex of Nutall, Laud, Florentino and Mendocino, natives had many different uses for agave and its sub-products: food, threads, needles, shoes, roof tops, clothes, nails, weapons and paper among others. The seeds have been ground into powder to make bread or to thicken soup.

In 1577, the Spanish explorer Francisco Hernández wrote about the maguey in the central highlands of Mexico: "As a whole (maguey) can be used as fuel or to fence fields. Its shoots can be used as wood and its leave as roofing materials, as plates or platters, to make paper, to make cord with which they make shoes, cloth, and all kinds of clothes…. From the sap…they make wines, honey, vinegar, and sugar…From the root, they also make very strong ropes which are useful for many things. The thicker part of the leaves as well as the trunk, cooked underground…are good to eat…There is nothing which gives a higher return."

The agave is still used as food today, although it is not as critical to the natives as it was in the past. Agave syrup or nectar (aguamiel) has always been popular in Mexico, but in the past decade has become popular in the health food circles because it provides a good alternative to cane sugars that diabetics can also tolerate.

For millennia, the Hnahnu people used the agave as a source of material to produce more 100 different products including fibres for weaving, brushmaking and other crafts, construction materials, soap, small furniture, toys, ornaments, food and beverages, paper, medicinal products, firewood and even boundary markers in the countryside. The Hnahnu retain a deep traditional knowledge of the life-cycle, characteristics and uses of the agave.

Agave is still used as medicine, particularly in boticas - pharmacies - usually in alternative medicine boticas that offer natural or homeopathic remedies, often selling them beside religious icons and images on the same shelf. One botica online promises agave essence will cure "emotional immaturity, aggressive conduct, impatience, fatigue and premature aging. Before the mid-1800s, there were a dozen agave species used for tequila. But the producers were specializing, growing those that made the best economic as well as aesthetic product.

By the 1870s, the indigenous people of Mexico had so refined their cultivation practices that physiological ecologists of today have barely bettered them. By the 1870s tequila was reduced to the monoculture of blue agaves. In March, 2007, scientists at the University of Guadalajara have announced they believe the blue agave contains compounds that may be useful in carrying drugs to the intestines to treat diseases such as Crohn's disease and colitis.

Perhaps the biggest potential market for agave food products today is the growing agave nectar or syrup market. Agave syrup consists primarily of mostly the easily digested fructose and s smaller percentage of glucose, the amounts depending on the producer. It is sold as a sugar substitute in many health and grocery stores (agave syrup is three-four times sweeter than table sugar). While similar to honey, agave nectar's glycemic index is only 27, compared to honey at 83, which means it is absorbed more slowing into the bloodstream.

And ofcourse, the Agave is also used to produce Mezcal and Tequila !

But enough of sugar and other contents, I assure you that spinning this fibre blend does not impact negatively on your calory intake..lol .

Viva Frida Tops

A beautiful blend of Navajo Churro, Agave Cactus, Cashmere, angora bunny

100grams AU$25

The show must go on SOLD

Cosmic Wave SOLD

Cosmic Wave SOLD

A sunny Beach day SOLD

A sunny Beach day SOLD

Vampire Weekend ...sold

Vampire Weekend ...sold

Flamingoes in the Caribbean SOLD

Flamingoes in the Caribbean SOLD

Lavender Fields SOLD

Dragonfly in Amber Sold

Dragonfly in Amber Sold

Indigo SOLD

Indigo SOLD

Rose Velvet-SOLD-

Rose Velvet-SOLD-

Rainforest Dreams SOLD

Rainforest Dreams SOLD

Gem Corn Magic SOLD

Gem Corn Magic SOLD

Unicorn Puppies SOLD

Unicorn Puppies SOLD |

| Castlemilk Moorit Sheep (photo:RBST Caledonian Support Group) |

Castlemilk Moorit Sheep

Castlemilk Moorit sheep are the cutest most feisty little things. The Castlemilk Moorit sheep breed take their name from the Castlemilk estate in Dumfriesshire, where they originated in the early 1900s. They were originally bred to provide meat, wool to make clothing for the estate workers, and also to prance around the parklands of the estate. They are graceful, elegant sheep with fine, kemp-free wool, which is mid honey brown (moorit is a Scottish word for brown) at the base and bleached to a fawn colour at the tips.Castlemilk Moorit sheep have some Manx Loghtan sheep and mouflon sheep breed ancestry and have retained the interesting mouflon markings of white underbelly, lower jaw, knee, eye markings (‘spectacles’) and a white rump patch. They are also feisty and pretty fast!

Once clipped they look totally different – almost like deer – as they revert to the dark brown colour for a few weeks, until the growing fleece bleaches back to fawn at the tips. At one point in the early 1970s Castlemilk Moorits were reduced to only around 12 individuals and could easily have simply ‘disappeared’. However, those few remaining were rescued in two groups, including six ewes and two rams which were taken to Cotswold Farm Park. All of today’s Castlemilks, which include around 700 registered females, are descended from these two small groups.

In the past couple of years the breed has been downlisted from the ‘Endangered’ to the ‘Vulnerable” category on the RBST watchlist – a big success.

|

| Cute Castlemilk Moorit lambs 4th barrier island from the top right of the picture |

|

| lambs with their mum |

As with everything the way that you scour and process the fibre is very important. The fleece of the castlemilk moorit ranges from 28 to 32 microns and the staple length is about 6 cms. The outer edges of the staple are often bleached by the sun and the locks often have a pointy tip. I find it very easy to spin. It reminds me of Manx Loughtan but definitely finer and softer. It is not that easy to get hold of this quality fibre so I only have a limited amount, but it is oh so worth it !

Warning : There is only a very limited quantity available.

Castlemilk Moorit Sheep Tops

100+gram tops, Natural AU$23. SOLD

VICUNA BLEND TOPS

|

| Vicuna in the Ecuadorian Highlands |

The Vicuna belongs to the camelid family, like the alpaca and the guanaco, but lives in the wild at an altitude of more than 4000 meters above sea level. You can find vicunas from as far north as Ecuador, Chile and Argentina. The vicuna is the smallest of the 4 south American camelids (Vicuna, guanaco, alpaca and llama). The colour of their fibre is caramel in colour with a white bib below their face. Their height is between 1 to 1.3 meters and they weigh approximately 35 to 40 kilos. Their fibres are classified as one of the most finest in the world with a micron count of appr 9 to 12micron with a staple length of about 3cms. You can find the vicuna in three kinds of social groups: the polygamous groups with 1 male and 10 females; a group of males and then there are the solitary males. The gestation period for vicunas is about 10 to 11 months.

|

| a small herd of male vicunas |

Centuries ago, the Inca harvested prized vicuña fibre by harmlessly shearing the animals, which they considered sacred. The exquisitely soft but ultra-warm garments created from vicuña wool were reserved for rulers/emperors, under threat of death for violators.

When the Spanish arrived, they were equally entranced by the fibres, but in keeping with their violent conquest of the Incan Empire in the 16th century, they simply killed vicuñas to access their wool. That method persisted until the 1960s, when just 10,000 vicuñas remained.

Realizing that the species was in danger of imminent extinction, conservationists and vicuña range-state governments began scrambling to save it; first by protecting the animals and outlawing trade in their wool; then in the 1990s and 2000s, by launching programs that harkened back to the old way of doing things: introducing community-led efforts to harmlessly and sustainably shear vicuñas and manage populations.

At first, the plan seemed to be working. Locals worked together to harvest the wool, which they then used to make handicrafts or sold to textile companies in Italy, Scotland and Japan. “The program started quite well, but for the past 15 years we’ve discovered a series of fundamental problems,” says Cristian Bonacic, currently a visiting professor at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and permanently based at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile.

Communities working directly with vicuñas, most of which are extremely poor, currently receive little profit for all their effort — “the smallest piece of the pie,” says Daniel Elias Maydana, a technical advisor for the National Association of Vicuña Fibre Producers who works in Bolivia and northern Argentina. “The money obtained from managing vicuñas is important, but it’s certainly not sufficient to lift families out of poverty.”

When the Spanish arrived, they were equally entranced by the fibres, but in keeping with their violent conquest of the Incan Empire in the 16th century, they simply killed vicuñas to access their wool. That method persisted until the 1960s, when just 10,000 vicuñas remained.

Realizing that the species was in danger of imminent extinction, conservationists and vicuña range-state governments began scrambling to save it; first by protecting the animals and outlawing trade in their wool; then in the 1990s and 2000s, by launching programs that harkened back to the old way of doing things: introducing community-led efforts to harmlessly and sustainably shear vicuñas and manage populations.

At first, the plan seemed to be working. Locals worked together to harvest the wool, which they then used to make handicrafts or sold to textile companies in Italy, Scotland and Japan. “The program started quite well, but for the past 15 years we’ve discovered a series of fundamental problems,” says Cristian Bonacic, currently a visiting professor at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and permanently based at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile.

Communities working directly with vicuñas, most of which are extremely poor, currently receive little profit for all their effort — “the smallest piece of the pie,” says Daniel Elias Maydana, a technical advisor for the National Association of Vicuña Fibre Producers who works in Bolivia and northern Argentina. “The money obtained from managing vicuñas is important, but it’s certainly not sufficient to lift families out of poverty.”

|

In 2014, for example, Peru exported 10 tons of vicuña fibre to Italy, for which all Peruvian communities combined received a grand total of $250,000. “That is ridiculously small,” Bonacic says.

A single coat, using just two kilos (4.4 pounds) of wool, can cost $50,000, he says, meaning that the fashion industry’s revenue from just five garments can equal the entire earnings that the whole of Peru’s vicuña-producing communities sees in a year.

Another tit-bit of information: there was even a political scandal called the “Vicuna coat Affair”: In 1958, Sherman Adams, President Dwight Eisenhower's forceful chief of staff, was one of Washington's most influential men. His career, however, ended abruptly after he accepted an overcoat from a textile magnate under federal investigation. The gift might seem innocuous enough, but the coat in question was made of vicuña—an incredibly soft, light, rare and very expensive yarn. It was alleged that Mr. Adams, swayed by such luxurious gifts, subsequently tried to influence federal agencies on the magnate's behalf. Despite the politico's protestations of innocence, he resigned in a scandal that some dubbed the Vicuña Coat Affair.

Now, the silky vicuna fibre sits at the nose-bleed-high pinnacle of tailored luxury. Each year, only 13,000 to 17,500 pounds of vicuña become available. The Italian tailoring house Kiton makes only about 100 vicuña pieces a year; an off-the-rack sport coat costs at least US$21,000, while the price of a made-to-measure suit starts at US$40,000. A single vicuña scarf is about US$4,000. There are only 30 vicuña suits produced per year. Each is numbered, and the most affordable model goes for US$46,500.

A single coat, using just two kilos (4.4 pounds) of wool, can cost $50,000, he says, meaning that the fashion industry’s revenue from just five garments can equal the entire earnings that the whole of Peru’s vicuña-producing communities sees in a year.

Another tit-bit of information: there was even a political scandal called the “Vicuna coat Affair”: In 1958, Sherman Adams, President Dwight Eisenhower's forceful chief of staff, was one of Washington's most influential men. His career, however, ended abruptly after he accepted an overcoat from a textile magnate under federal investigation. The gift might seem innocuous enough, but the coat in question was made of vicuña—an incredibly soft, light, rare and very expensive yarn. It was alleged that Mr. Adams, swayed by such luxurious gifts, subsequently tried to influence federal agencies on the magnate's behalf. Despite the politico's protestations of innocence, he resigned in a scandal that some dubbed the Vicuña Coat Affair.

Now, the silky vicuna fibre sits at the nose-bleed-high pinnacle of tailored luxury. Each year, only 13,000 to 17,500 pounds of vicuña become available. The Italian tailoring house Kiton makes only about 100 vicuña pieces a year; an off-the-rack sport coat costs at least US$21,000, while the price of a made-to-measure suit starts at US$40,000. A single vicuña scarf is about US$4,000. There are only 30 vicuña suits produced per year. Each is numbered, and the most affordable model goes for US$46,500.

|

| Handspun and handwoven vicuna and cashmere scarf, the price to the end consumer US$17.000 , the reward given to artists and poor communities ensuring the ethical shearing of vicunas: a tiny, tiny fraction . spin and weave your own ethically |

In 2008, a high end Italian fashion house established an eight-square-mile reserve to study the animals. And earlier this year, the company took a controlling stake in Sanin SA, an Argentinean firm that has the rights to shear around 6,000 wild vicuña living on a 328-square-mile territory in the country's Catamarca province. It's part of it's long-term strategy to establish large reserves where the local people can protect, breed and shear vicuña ethically.

Vicuñas are now listed as a species of “Least Concern” according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, but most experts agree that there is cause for concern. Vicuña populations now hover at 400,000 to 500,000 animals, but their numbers have remained stagnant or — in the case of Chile — declined over the past two decades.

Vicuñas are now listed as a species of “Least Concern” according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, but most experts agree that there is cause for concern. Vicuña populations now hover at 400,000 to 500,000 animals, but their numbers have remained stagnant or — in the case of Chile — declined over the past two decades.

|

“It’s true that populations are large, but they’re far less than the 7 to 8 million that we should have,” Bonacic says. “I seriously think that if poaching continues to increase, some populations may go extinct.”

As in everything in this world, we as consumers and fibre artists have to be aware of where the fibre comes from but more than anything to realise that everything comes at a price: there is no way that handpicked, hand carded, fibres of a rare breed that is carefully hand sheared can be offered with low prices.

What we see happening all over the world is that the wealthy end consumer pays a huge amount of money of which only a tiny fraction goes to the preservation and the maintaining of the natural habitat and the poor communities that live off the land. We all have to be conscious that this attitude has to change.

I have been trying to do my bit with bringing rare breeds to you and trying to tell you the story of how importantant it is to preserve and protect. You may think how can 1 person change something? But I truly believe you can. We all can make a change together. So with this story of this truly royal and exquisite animal, I offer you a magnificent blend. Do your bit and help this amazing animal survive and make life better for numerous poor communities who are doing the right thing.

A beautiful blend of Vicuna (40%), Muga Silk (30%), Cashmere(30%)

28grams in a nice gift package

AU$60

SOLD OUT

to put this price in perspective: 28 grams of pure vicuna is priced at around US$250 !

vicuna blend top

As in everything in this world, we as consumers and fibre artists have to be aware of where the fibre comes from but more than anything to realise that everything comes at a price: there is no way that handpicked, hand carded, fibres of a rare breed that is carefully hand sheared can be offered with low prices.

What we see happening all over the world is that the wealthy end consumer pays a huge amount of money of which only a tiny fraction goes to the preservation and the maintaining of the natural habitat and the poor communities that live off the land. We all have to be conscious that this attitude has to change.

I have been trying to do my bit with bringing rare breeds to you and trying to tell you the story of how importantant it is to preserve and protect. You may think how can 1 person change something? But I truly believe you can. We all can make a change together. So with this story of this truly royal and exquisite animal, I offer you a magnificent blend. Do your bit and help this amazing animal survive and make life better for numerous poor communities who are doing the right thing.

Vicuna Blend Tops

A beautiful blend of Vicuna (40%), Muga Silk (30%), Cashmere(30%)

28grams in a nice gift package

AU$60

SOLD OUT

to put this price in perspective: 28 grams of pure vicuna is priced at around US$250 !

vicuna blend top

Vicuna and it’s packaging

A beautiful blend of Australian Superfine Merino (70%) and Australian Cashmere (30%)

each cone weighs over ONE kilo, 1200 metres /100grams.

SOLD OUT

Absolutely perfect for lace knitting, weaving and felting ! This yarn is also amazing to use to ply your handspun yarns with, to autowrap your art yarns and so much more!! Also great for making lace and tatting !! Australian grown and processed.

Cashmerino Lace Yarn Cones Special Bendigo Show Special !!! AU$129 (Normal price per 100grams is $32!!!!)

A beautiful blend of Australian Superfine Merino (70%) and Australian Cashmere (30%)

each cone weighs over ONE kilo, 1200 metres /100grams.

SOLD OUT

Absolutely perfect for lace knitting, weaving and felting ! This yarn is also amazing to use to ply your handspun yarns with, to autowrap your art yarns and so much more!! Also great for making lace and tatting !! Australian grown and processed.

NEW RANGE !!!! IxCHeL PRINCESS BRIDE Tweed fingering weight yarn

Super soft lambswool

Spun singles, fingering or sock weight yarn

+/- 200meters/218yards

50grams 1.76oz

AU$16

As you Wish

True Love

Princess in Training

Mawwage SOLD

Inconceivable

have fun storming the castle

All my contact details are here:

Please don't hesitate to contact me at any time if you have any questions okay? Always happy to enable. All my contact details are to be found at the end of this week’s blog entry.

Have a fun weekend !!!

Have a fun weekend !!!

How To Order:

1. You can email me on ixchelbunnyart at gmail dot com or ixchelbunny at yahoo dot com dot au

2. Message me on facebook or

3. Message me on www.ravelry.com where I am ixchelbunny.

4. message me on Instagram where I am @ixchelbunny

I will email you right back with all your order details and payment methods.

Any questions? Any custom orders for yarn or dyeing fibre? : Please don’t hesitate to ask! Always happy to enable.

2. Message me on facebook or

3. Message me on www.ravelry.com where I am ixchelbunny.

4. message me on Instagram where I am @ixchelbunny

I will email you right back with all your order details and payment methods.

Any questions? Any custom orders for yarn or dyeing fibre? : Please don’t hesitate to ask! Always happy to enable.

Dates to put in your Calendar

SEPTEMBER 2020 !!!

THE LAUNCH OF

THE BUNNY SPECTACULAR !!

MORE INFO VERY VERY SOON !!!!!!

Keep your eyes out for any news on the

ixchelbunny Instagram feed and the IxCHeL facebook page!!

RABBIT ON !

((hugs))

Charly

No comments:

Post a Comment